Why ransomware victims pay, and what smart organisations do instead

Ransomware extortion follows rational economics, not random chaos. When assets are valuable, defences are weak, and consequences for attackers are low, extortion thrives. This pattern holds whether the extortionist is the Sicilian Cosa Nostra or a ransomware group operating from a server in St Petersburg.

Many pages have been written about whether or not breached organisations should pay the ransom, and there is lots to be read about why victims pay. But the BIG question is this: Why so many organisations remain unprepared despite years of warnings, record breach volumes, and a regulatory landscape that now imposes direct financial consequences for inadequate security?

The economics of extortion Today

It’s happening all the time! In just the last six months, an average of 9 organisations with turnovers in excess of $3M, paid their ransoms each month. And that stat only references the organisations that end up on the Department of Home Affairs records.

In the physical world, extortion is a well-studied economic phenomenon. From the Sicilian Cosa Nostra to the Yakuza-linked protection rackets in Japan’s nuclear power industry, criminal organisations treat extortion as a legitimate revenue stream. The economics are consistent: when assets are valuable to their owners, easily accessible and poorly protected, and the risk of consequences for the attacker is low, extortion thrives. Academic research into extortion racket systems confirms these dynamics hold across cultures and centuries (Elsenbroich et al., 2016; Frazzica et al., 2014).

The Internet is no different. Ransomware and cyber extortion succeed under identical conditions. If an organisation holds valuable data, has poor defences, and the attacker faces minimal risk of identification or prosecution, the conditions for extortion are met. The only things that have changed are scale and speed: a criminal group can now target thousands of organisations simultaneously from the other side of the planet.

Australia's costly wake-up calls

The Optus breach and the Medibank hack were the first time large numbers of Australians experienced ransomware consequences first-hand. Then Cyber Security Minister Clare O’Neil described the Medibank breach as the most devastating cyber attack Australia had experienced as a nation, admitting the country was “a decade behind other developed countries” on cyber security.

The consequences for Medibank have been severe and long-running with APRA imposing an additional $250 million capital adequacy requirement. The OAIC filed civil penalty proceedings alleging Medibank failed to take reasonable steps to protect customer data, noting the company’s cyber security budget had been just AU$1 million against revenue of AU$7.1 billion. A joint police operation linked over 11,000 cybercrime incidents to the Medibank data breach. By mid-2024, Medibank had spent over $86 million on breach-related costs and expected to exceed $125 million, with years of litigation ahead.

But if Optus and Medibank were the wake-up call, many organisations slept through the alarm. In May 2024, electronic prescription provider MediSecure suffered a ransomware attack that compromised the personal and health information of approximately 12.9 million Australians, roughly half the country’s population. The breach involved 6.5 terabytes of exfiltrated data including patient names, dates of birth, Medicare numbers, and prescription details. MediSecure sought government funding for breach response, was refused, and entered voluntary administration in June 2024. Its data was listed for sale on the dark web for US$50,000. MediSecure was not just breached; it ceased to exist.

The ASD Annual Cyber Threat Report for FY2024-25 reported over 84,700 cybercrime reports (one every six minutes), responded to over 1,200 cyber security incidents (up 11%), and noted that ransomware incidents against the healthcare sector had doubled year on year. Data breaches reported to the OAIC hit record highs in 2024, with over 1,100 breaches representing a 25% increase from 2023.

And data collected from the Department of Home Affairs in February 2026 shows that breaches and ransom payments are continuing to rake in the payments, with itnews revealing that “75 Australian businesses with a turnover of more than $3 million have admitted paying off ransomware groups in the first eight months of mandatory disclosure.“

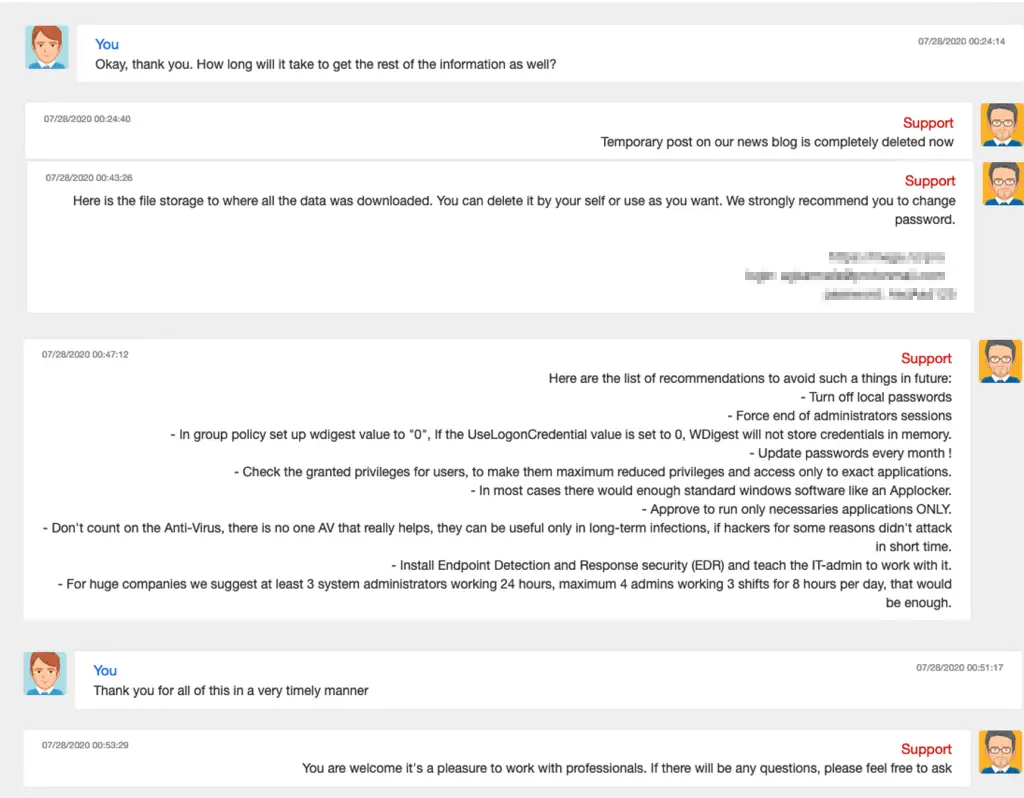

CWT chats with the Ragnar Locker attackers, as they negotiate payment

Why organisations pay

Research by Connolly and Borrion, examining 39 ransomware attacks using qualitative data from victims and UK police cybercrime units, found that victims make rational cost-benefit decisions. When critical data is encrypted, backups are unavailable, and the alternative is business closure or crippling operational disruption, payment becomes the rational choice (“Your Money or Your Business”, ICIS 2020). Their research illustrated two contrasting scenarios: a private business that paid because all vital operations had ceased and there were no backups, and a public organisation that chose not to pay but later reflected that the recovery was so challenging (over a year) that a private business in the same position would not have survived.

Current data tells a nuanced story. According to the Sophos State of Ransomware 2025 report, nearly 50% of organisations that were hit paid the ransom, the second highest rate in six years. The median ransom payment was US$1 million, down 50% from US$2 million in 2024, reflecting both increased negotiation by victims and disruption of major ransomware groups. Encouragingly, 44% of organisations stopped attacks before data was encrypted, a six-year high.

Globally, total ransomware payments fell to US$813 million in 2024, down 35% from the record US$1.25 billion in 2023, driven by increased law enforcement actions and improved victim resilience (Chainalysis, 2025).

But the overall trend conceals a troubling reality. The average cost to recover from a ransomware attack (excluding the ransom itself) was US$1.53 million in 2025. Only 54% of organisations used backups to restore their data, the lowest percentage in six years. And 69% of organisations that paid a ransom were subsequently attacked again.

The uncomfortable truth about trusting criminals

A common argument against paying ransoms is that you cannot trust criminals to follow through. But research and evidence suggest this is more complicated than it sounds.

Successful extortion operations, whether physical or digital, depend on reputation. The attacker needs victims to believe that compliance will produce the promised result; otherwise, nobody pays. Real ransomware gangs establish and maintain a reputation for delivering on their commitments, because their business model depends on it.

The 2020 CWT (formerly Carlson Wagonlit Travel) ransomware incident provides a remarkable illustration. The Ragnar Locker group attacked CWT, stole approximately 2 terabytes of data, and initially demanded US$10 million. CWT negotiated through a publicly accessible online chatroom, citing financial difficulties related to COVID-19, and agreed on a payment of US$4.5 million in Bitcoin. After receiving payment, the attackers provided decryption tools, shared the credentials to access the stolen data for deletion, and provided a summary of the vulnerabilities they had exploited along with recommendations for improving CWT’s security posture.

None of this means paying is a good outcome. Only 54% of organisations that paid in 2025 recovered via ransom-provided decryption (many still needed backups), and nearly 70% of those who paid were attacked again. The point is narrower: “you can’t trust criminals” is not the strongest argument against paying, because some of them are, in their own perverse way, reliable enough to sustain a business model. The strongest argument against paying is that you should never have to be in that position in the first place.

The regulatory landscape is catching up

Australia’s regulatory response to ransomware has accelerated significantly. Since May 2025, mandatory ransomware payment reporting has been in effect under Part 3 of the Cyber Security Act 2024 (Cth). Businesses with annual turnover exceeding $3 million and entities responsible for critical infrastructure assets must report any ransomware or cyber extortion payment to the Australian Signals Directorate within 72 hours of making it. From January 2026, the Department of Home Affairs has moved to active compliance and enforcement.

Paying a ransom is no longer a quiet, private decision; it is a reportable event. And the broader legislative direction makes inadequate security preparation an increasingly expensive position to hold.

The Privacy and Other Legislation Amendment Act 2024 introduced OAIC infringement notices of up to $66,000 per contravention, new search and seizure powers, and a statutory tort for serious invasions of privacy. The new statutory tort creates a personal right for individuals to sue where their privacy has been seriously invaded, opening a direct avenue for class actions following large-scale data breaches.

The Australian government has also demonstrated willingness to pursue attackers internationally. Cyber sanctions were imposed on Russian national Aleksandr Ermakov and five additional individuals linked to the Medibank breach, alongside ZServers, the infrastructure provider used in the attack. Law enforcement actions have had a tangible impact on the broader ecosystem: the takedown of LockBit and the collapse of ALPHV/BlackCat in 2024 contributed to the 35% drop in total ransomware payments that year.

Drive it like you own it

Cyber risk is a business risk, not an IT problem. As business owners, one of our core responsibilities is to manage risks to business reputation and continuity. In theory, risks can be:

Avoided. Not really applicable here, unless your business has somehow travelled back to the pre-Internet era.

Transferred. Typically done through cyber insurance, but coverage increasingly depends on the business demonstrating an adequate level of cyber security maturity. According to Sophos, 42% of organisations with cyber insurance found their policies covered only a small portion of ransomware damages.

Managed (reduced). This is where the business is proactive and establishes a well-managed, reasonably funded maturity improvement plan to reduce cyber risks to an acceptable level. Frameworks such as the ACSC Essential Eight, CIS 18 Critical Security Controls, and ISO 27001 provide structured approaches to building this maturity.

Accepted. This is where the organisation has a formal security plan, risk register, and associated risk management plan, and can be confident that it has managed or transferred the risks that cannot be accepted. Risk acceptance should be a conscious, documented, board-level decision, not the result of ignorance or neglect.

As FBI Director Robert Mueller observed at RSA in 2012: “There are only two types of companies: those that have been hacked, and those that will be.” But his advice was not given so we could throw our hands up in hopelessness. It was a prescient warning to prepare. The organisations that survive ransomware attacks are the ones that invested in preparation before the attack arrived. They have tested backups that work. They have incident response plans that people have practised. They have security controls proportionate to their risk. They have board-level visibility and accountability. And when something does go wrong, they recover in days rather than months, often with the support of a managed SOC and SIEM capability that provides continuous monitoring and rapid incident response.

The bottom line

The organisations that do not survive are the ones that treated cyber security as an IT cost centre, a box-ticking exercise for an annual audit, or somebody else’s problem. MediSecure is the most sobering Australian example: not just breached but destroyed, unable even to afford the cost of telling its 12.9 million affected customers what had happened to their data.

Mueller made his observation thirteen years ago. If your organisation still has not taken this seriously, the question is not whether something will happen. It is what you are going to do about it before it does.

dotSec works with organisations across Australia to identify, manage, and reduce cyber security risk, from cyber maturity assessments and penetration testing through to managed security operations. If you want to understand where your organisation stands before an attacker shows you, get in touch.

References

[1] ASD Annual Cyber Threat Report 2024-25

[2] Sophos, State of Ransomware 2025

[3] Chainalysis, Crypto Ransomware 2025: ransomware payment trends

[4] Connolly & Borrion, “Your Money or Your Business: Decision-Making Processes in Ransomware Attacks”, ICIS 2020

[5] Elsenbroich et al., “The Extortion Relationship: A Computational Analysis”, JASSS 2016

[6] Frazzica et al., “How Mafia Works: An Analysis of the Extortion Racket System”, ECPR 2014

[7] Privacy and Other Legislation Amendment Act 2024 (Ashurst analysis)

[8] Australian Privacy Alert: Parliament passes major privacy law reform (Norton Rose Fulbright)

[9] Mueller, R.S., RSA Cyber Security Conference, March 2012

Premier australian cyber security specialists

ISO 27001 consulting

Practical and experienced Australian ISO 27001 and ISMS consulting services. We will help you to establish, implement and maintain an effective information security management system (ISMS).

Penetration tests

DotSec’s penetration tests are conducted by experienced, Australian testers who understand real-world attacks and secure-system development. Clear, actionable recommendations, every time.

PCI DSS

dotSec stands out among other PCI DSS companies in Australia: We are not only a PCI QSA company, we are a PCI DSS-compliant service provider so we have first-hand compliance experience.

WAF and app-sec

Web Application Firewalls (WAFs) are critical for protecting web applications and services, by inspecting and filtering out malicious requests before they reach your web servers

Identity management

Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA) and Single Sign-On (SSO) reduce password risks, simplify access, letting verified and authorised users reach sensitive systems, services and apps.

Vulnerability management

dotSec provides comprehensive vulnerability management services. As part of this service, we analyse findings in the context of your specific environment, priorities and threat landscape.

Phishing and soc eng

We don’t just test whether users will click a suspicious link — we also run exercises, simulating phishing attacks that are capable of bypassing multi-factor authentication (MFA) protections.

Penetration testing

DotSec’s penetration testing services help you identify and reduce technical security risks across your applications, cloud services and internal networks. Clear, actionable recommendations, every time!

Managed SOC/SIEM

dotSec has provided Australian managed SOC, SIEM and EDR services for 15 years. PCI DSS-compliant and ISO 27001-certified. Advanced log analytics, threat detection and expert investigation services.

Secure configuration

We provide prioritised, practical guidance on how to implement secure configurations properly. Choose from automated deployment via Intune for Windows, Ansible for Linux or Cloud Formation for AWS.

Secure cloud hosting

Secure web hosting is fundamental to protecting online assets and customer data. We have over a decade of AWS experience providing highly secure, scalable, and reliable cloud infrastructure.

Essential eight

DotSec helps organisations to benefit from the ACSC Essential Eight by assessing maturity levels, applying practical security controls, assessing compliance, and improving resilience against attacks.

CIS 18 Critical Controls

Evaluation against the CIS 18 Controls establishes a clear baseline for stakeholders, supporting evidence-based planning, budgeting, maturity-improvement and compliance decisions

Advisory services

We have over 25 years of cyber security experience, providing practical risk-based guidance, advisory and CISO services to a wide range of public and private organisations across Australia.